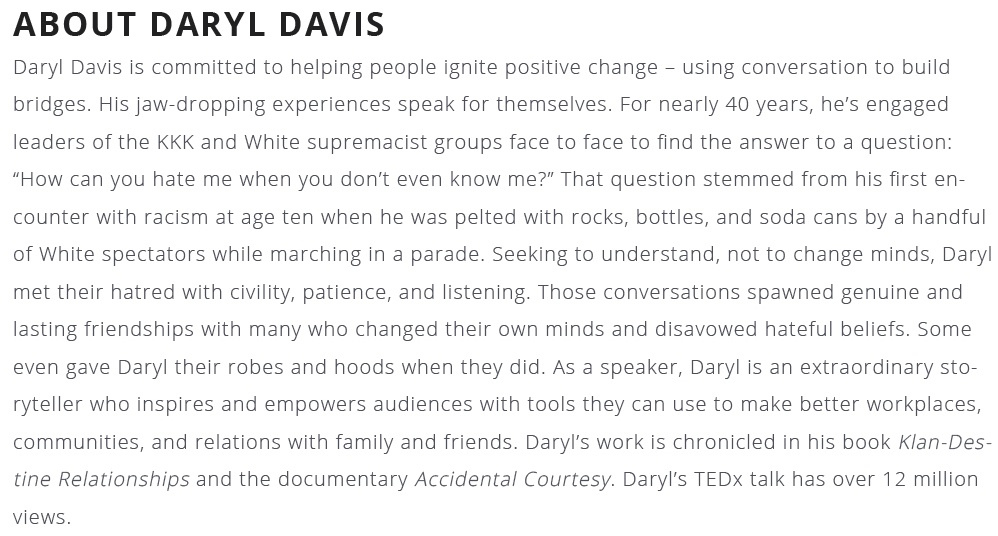

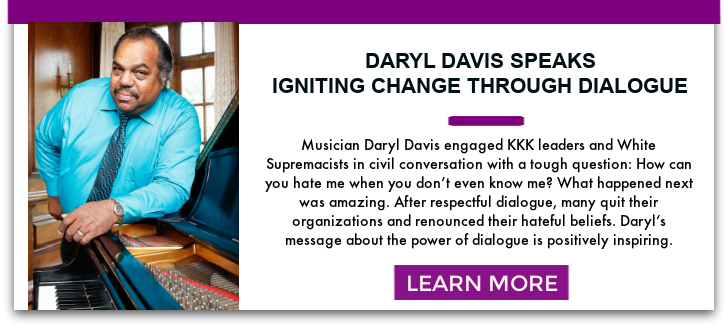

HOW CIVIL CONVERSATIONS CAN CHANGE THE WORLD - DARYL DAVIS

CIVIL CONVERSATIONS MAKE A DIFFERENCE IN POLARIZING TIMES

How can we lower the emotional temperature at a time when people find themselves at odds with one another about so many issues - in their communities, at work, and at home? DARYL DAVIS has an answer: Get to know those who don’t share your values. Really get to know them!

Daryl should know. A Black musician who befriended KKK leaders and other white supremacists, he built unlikely bridges with those who hate him just because of the color of his skin. And as unimaginable as that seems, many of those haters became true friends and renounced their old beliefs – some even gave Daryl their robes and hoods.

BOOK DARYL DAVIS TO SPEAK AT YOUR NEXT EVENT

In the process, Daryl has unearthed some universal truths about conflict, hate, intolerance, and communication that are invaluable in today's world. His extraordinary journey is chronicled in his first book, Klan-Destine Relationships, and the documentary about his encounters, Accidental Courtesy. As a speaker, Daryl’s impact on audiences is profound – his TEDx talk has millions of views.

In his keynote talks and workshops, Daryl offers lessons that help people build better workplaces, communities, and relations with family and friends. “If I can sit down and talk to KKK members and neo-Nazis and get them to give me their robes and hoods and swastika flags and all that kind of crazy stuff, there’s no reason why somebody can’t sit down at a dinner table and talk to their family member about anything.”

A CONVERSATION WITH DARYL DAVIS, CONFLICT NAVIGATOR

What set you off on this unusual path?

When I was a 10-year-old Cub Scout, I was the only Black participant in an otherwise all-white parade. I was pelted with rocks, bottles, and soda pop cans by just a few white spectators in the otherwise large crowd who are mostly waving and cheering all the marchers in the parade. This led me to ask my parents a very simple question at the age of 10: “How can they hate me when they don't even know me?”

You never encountered that kind of thing before?

It was totally alien to me. I grew up as a child of parents in the U.S. Foreign Service. We lived and traveled all over the world. The kids I associated with were from all kinds of cultures and religions and skin colors. It wasn’t until I returned to the U.S. that I learned the color of my skin is a big issue for some people.

Did you encounter racism professionally?

Music is a pretty color-blind profession. You routinely play with all kinds of people. After I graduated college with my degree in music, I once again traveled all over the world performing. In total, I've been in 57 different countries on six continents and 49 of 50 States. In my travels, I've encountered people who don't look like me, don't speak the same language, don't worship as I do, and don't practice the same culture. Given my early life living in different countries, it was just a normal and natural thing.

What did that teach you?

We are all human beings. And I came to the conclusion we all want the same basic five things in our life. We all want to be loved. We all want to be respected. We want to be heard. We want to be treated fairly. And we want the same things for our family as anybody else wants for their family.

How did you come to know people in the KKK?

Years ago, after one of my performances in Maryland, I was approached by a white gentleman who told me that this was the first time he'd ever heard a Black man play piano like Jerry Lee Lewis. I explained to him that both Jerry Lee and I were influenced by Black blues and boogie-woogie piano players. That's where rock and roll and rockabilly evolved. He didn’t believe in the Black origin of that style of music; even after I told him that Jerry Lee Lewis was a good friend and had told me himself of his influences. Then, over a drink, the gentleman revealed something about himself: He said he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

This was a serendipitous opportunity to ask my burning question – How can you hate me when you don’t even know me? I mean, who better to ask my question of than someone who would go so far as to join an organization with a 156-year history of hating people who don't look like them, and hating those who don't believe as they believe. He put me in touch with the leader of the KKK in Maryland and I was able to pose my question to him directly – face-to-face. That was the start of it.

What did you do after that?

For almost four decades, I have been traveling the country, interviewing KKK Grand Dragons, Imperial Wizards, and other members, and attending Klan rallies. At those rallies, I engage in civil conversation. I truly believe that we spend way too much time in this country talking about the other person, talking at the other person, or talking past the other person. We really need to spend a little bit of time talking with the other person. And when I engage in civil dialogue, I try to employ some of those five principles I just told you about. There’s a great video of me at a rally CNN took which makes the point.

The CNN news video was very revealing. There was a lot going on there.

There was, indeed. Did you hear the Klan leader say that he respected me? I'm a Black guy! He's the head of the Klan. What's that all about? What he said was, "While we may not agree on everything, at least he respects me to sit down and listen to me. And I respect him to sit down and listen to him." Those were his words. Very, very important.

If people don't get anything else out of that CNN video, I want them to notice that I showed him one of those core values: respect. He said I respected him, so he listened to me. Everybody wants to be heard. I listened to him. There's another core value: respect and being heard. I listened to him. He listened to me. Everybody wants to be treated fairly. There's your third core value.

Because I employed some of those five core values, the Klan leader decided he had been wrong over time, and he quit the Ku Klux Klan; and when he did, he gave me his robe and hood.

Photo by Rachel Chason/Washington Post

Photo by Rachel Chason/Washington Post

The power of conversation and engagement! And civility!

Right! This could never have been accomplished without dialogue and employing some of those five core values I mentioned earlier. When I first asked that Klan leader why he hated me when he didn't even know me, he gave me all kinds of answers that he felt justified his hatred for me and his perception that I was inferior just based on the color of my skin. But when he quit the Ku Klux Klan and gave me his robe and hood, his answer to my question, "How can you hate me when you don't even know me?" had changed. He no longer believed in what the Klan stood for. And he said that he really had no viable reason to hate me and that he had changed because of meeting me and our conversations. And he apologized.

Can you sum up what you’ve learned in almost 40 years of doing this?

I am a firm believer that a missed opportunity for dialogue is a missed opportunity for conflict resolution. Every one of us has a cell phone and email. Press a few numbers, hit a few words, hit send, and you're talking to people halfway across the country, in Europe, in China in South America, Africa, Australia, wherever you want to talk. We, Americans, invented that technology. So how is it that we Americans can talk to people as far away as the moon and all the way around this planet, but yet we have difficulty talking to the person who lives right next door because they are of a different color, a different religion, a different persuasion, speak a different language, or perhaps even one of our own family members at the dinner table who voted for a different candidate?

I think we spend too much time addressing the destruction, the anger, the hatred, and the fear when the root cause is ignorance. If we cure ignorance, then there's nothing to fear. With nothing to fear, there's nothing to get to hate and get angry about. With nothing to hate and get angry about, there's nothing to destroy.

The good thing is there is a cure for ignorance. That cure is called education and exposure. When you provide people with exposure to the things of which they are ignorant, you're also providing them with an education.

What does the future look like? Are we making progress on dealing with bias and hate?

Our country can only become one of two things. One, it can become that which we sit back and watch it become. Or two, it can become that which we stand up and make it become. In my speeches I ask people a question: Do you want to sit back and see what your country becomes or do you want to stand up and make your country become what you want to see? I ask them to think about it and when they wake up in the morning, get started on fulfilling their answer.

Any final thoughts?

Since I've started this kind of work, over 200 white supremacists have renounced their racist ideology and have given me their robes, hoods, Neo-Nazi flags, and other symbols of racism. I am not a psychologist, nor am I a sociologist. I'm just a rock and roll, boogie-woogie, piano pounder. So, if I can do it, so can you.

About Tony D'Amelio

Tony has spent his career putting talented people and audiences together, first in the music business and later representing the world's leading speakers. After concluding 27 years as Executive Vice President of the Washington Speakers Bureau, Tony launched D'Amelio Network, a boutique firm that manages the speaking activities of a select group of experts on business, management, politics and current events. Clients include: Mike Abrashoff, Mariana Atencio, Chris Barton, Lisa Bodell, Geoff Colvin, Daryl Davis, Suneel Gupta, Ron Insana, Katty Kay, Polly LaBarre, Nicole Malachowski, Ken Schmidt, and Bob Woodward.

.png)

.jpg)